One hundred years ago this year, the deadliest pandemic flu the world has ever seen swept around the globe, infecting about a third of the world’s population and killing some 20 to 50 million people, including about 675,000 in the U.S.

First observed in Europe, America, and areas of Asia, the disease came to be known as the “Spanish Flu,” probably because Spain was particularly hard hit and was not subject to the World War I news blackouts that kept the word of the disease in other countries from getting out.

Previously healthy young people were disproportionally affected, with officials estimating about 40 percent of U.S. Navy servicemen and 36 percent of those in the Army contracted the illness.

Research conducted in 2008 finally helped explain why the 1918 flu was so deadly: a group of three genes enabled the virus to weaken the bronchial tubes and lungs and led to the bacterial pneumonia that ultimately took so many lives.

Wakeup call

AARC Historian Trudy Watson, BS, RRT, FAARC, who just created a new gallery for the AARC’s Virtual Museum featuring the pandemic, says the 1918 outbreak was a wakeup call for health care professionals.

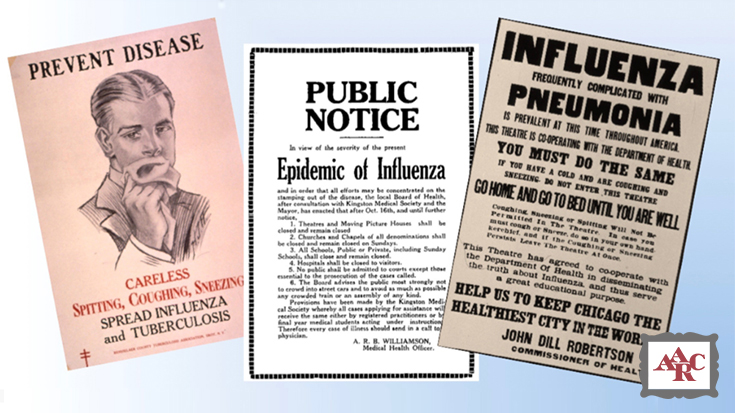

“Many of the basic lessons learned from the 1918 influenza pandemic are reflected in common practice today: covering coughs, frequent hand washing and/or using hand sanitizers, and using appropriate personal protective equipment,” Watson said.

She notes surveillance programs to monitor the number and location of influenza cases evolved after the 1918 influenza outbreak as well, and some of the practices that were put in place to combat the spread of the flu back then are still in use today.

“As in 1918 when schools, church services, and other community activities were canceled in the hope of reducing the spread of influenza, we witnessed similar temporary closures in communities where flu cases were prevalent during the recent 2017-2018 flu season,” says Watson.

Those preventative measures spill over to health care facilities too.

“Many health care facilities discourage and restrict visitors at the peak of flu season to minimize transmission and strongly encourage staff to remain at home if they experience influenza symptoms,” she said.

New focus on vaccines

Perhaps the most significant advancement to come out of the pandemic, however, was a new focus on the development of vaccines that could prevent the disease from occurring. While several decades would pass before these vaccines and other treatments like antibiotics would be ready for public use, the ball was set in motion.

The first flu vaccine came on the market in 1938 and was quickly followed by other vaccines and antibiotics: streptomycin for the treatment of tuberculosis in 1944, penicillin in 1945, the pertussis vaccine in the late 1940s, and the polio vaccine in 1952.

“The majority of these agents became available just as inhalation therapy was emerging as a profession,” Watson said. “Early inhalation therapy practitioners and physicians worked together to introduce new treatment modalities, develop equipment, and implement disease prevention techniques.”

RTs are key players

Many of those treatment modalities were driven by pulmonary pioneer Dr. Alvan Barach, whose interest in clinical oxygen therapy was sparked by experiences he had while witnessing the treatment of flu patients during his medical training in 1918-1919.

As he told Dr. Tom Petty in a 1979 interview, when it appeared that patients were 10 or 15 minutes away from death, he saw physicians hold a funnel about an inch away from their faces into which oxygen was bubbled from a low-pressure tank. While the young physician noted no benefit from this last-ditch effort, it got him thinking about whether oxygen could be effective with higher concentrations.

Dr. Barach’s research, coupled with that of other pioneers in the field, paved the way for the key role played by respiratory therapists in the battle against the annual outbreak of influenza today. Not only are therapists integral to the care delivered to people who are hospitalized with the condition, they also help educate their patients, the public, and even their own colleagues about the need for the annual flu vaccine.

“When the 1918 flu outbreak began, influenza vaccines simply did not exist,” Watson said. “Today, the CDC recommends that everyone over six months receive an annual flu vaccine. Health care professionals are encouraged, and in many cases, required to receive an annual flu vaccine for employment.”